The next consultant to visit your office may not be from McKinsey.

Second City Works managing partner Steve Johnston

Ali Khan is a corporate ninja. He has a black belt in Lean Six Sigma, an amalgam of two hypermethodical management systems developed by Toyota (Lean) and Motorola (Six Sigma).

Khan is all in: To get his belt, he had to pass 13 exams proving he could read a Pareto chart and use Kanban analysis. As a Lean Six Sigma process director at Sun Life Financial in Toronto, he teaches the stuff. But he recently had his mind blown by another, more unusual corporate tool: improvisational theater.

In April, a team of actors from The Second City, the Chicago theater company that launched Steve Carell, Amy Poehler, John Belushi, and Gilda Radner, came to Sun Life to help lead part of a three-day training session. At one point, an actor mimicked putting something imaginary at Khan’s feet and said: “Here is a box. What’s in it?”

“There’s a flower inside,” Khan said.

“What do you want to do with it?”

“I want to give it to you.”

Khan, 43, describes the simple exchange in tones of the sublime, as though it changed his life. And in fact, it did, he says. In another exercise, everyone clapped whenever a Sun Lifer said something. “You know it’s not real, but it feels awesome,” Khan says. And it led him to this: “Instead of judging your co-worker, you collaborate. You build on each other’s capabilities.”

Few hard-charging business leaders have put imaginary boxes at their employees’ feet (or paid anyone else to), but they should, says Steve Johnston, managing partner at Second City Works, the theater’s corporate-training subsidiary. Clients, including Google, Farmers Insurance, and Dow Chemical, are using improv techniques to foster communication, collaboration, and creativity. These are not necessarily skills MBAs are learning in business schools. “They come out really strong on the quant skills,” Johnston says, “but not so much on the soft ones.”

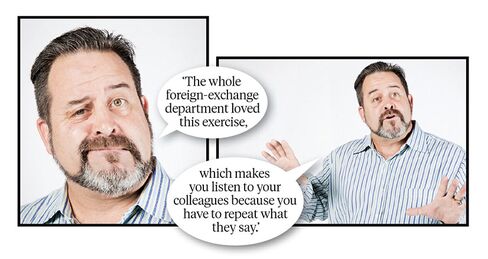

Trainers and executives from Second City Works do an improv exercise called repetition.

So what is improv, exactly? Say the word to later baby boomers and Gen Xers and you conjure memories of comedians on TV’s An Evening at the Improv. Almost none of that was improv, though. It was performers doing jokes they had rehearsed for months. True improv was born during the Depression in the slums of Chicago, where a woman named Viola Spolin used what she called theater games to help immigrant children assimilate.

Her son Paul Sills and two friends appropriated the games and turned them into a comic art at The Second City, a theater they opened in an old Chinese laundry in 1959, aiming their split-second satire at Eisenhower, suburbia, and fallout shelters, according to The Second City Unscripted: Revolution and Revelation at the World-Famous Comedy Theater, by Mike Thomas. A year after the founding of the theater, The Second City started a workshop for training its actors. In 1985, it started training anyone willing to pay tuition.

One of the first people to use improv to loosen up corporations was Gary Hirsch, a Portland, Oregon, artist who plies his craft on local stages. In 1996, he was selling T-shirts inked with his work and caught the eye of a British advertising executive named Robert Poynton, who called Hirsch for a meeting the next day and asked him what else he did.

It’s not hard to see how Poynton would be taken with Hirsch. Built like a bald fireplug with a well-used gym membership, the 50-year-old has enough energy to power a Tesla Model S. He paints, he illustrates, and, as he told Poynton that day, he does improv.

“Can you do it with 90 people at a large ad agency in two months?” Poynton asked. Sure, Hirsch said, and he did. Shortly after, the pair started On Your Feet, an improv-based corporate-training firm.

From there, Hirsch and a group of improv believers under his direction took the show to other companies: Intel, Nike, Disney, Daimler. They’ve even done sessions at General Electric’s vaunted Crotonville, New York, center, the Shaolin Temple of corporate training.

Lori Heino-Royer, director of business innovation at Daimler’s truck unit in Portland, brings in OYF six times a year to work with executives, leading them through games like Swedish Story, in which they’re told to spin a yarn on the fly with words that people shout from the audience. It forces people to think quickly.

Woody Allen once said that 80 percent of success is showing up. Hirsch says improv works because you have to really show up—and pay attention. “Being relentlessly present is a survival mechanism for life, but people don’t remember it,” Hirsch says. “They don’t think about it, and they spend a lot of time preparing for things that don’t happen and being freaked out by things that do.”

Improv’s promise is that being present will mean noticing more and listening better, which in turn will lead to richer communication and, ultimately, better collaboration and more creativity. That’s the trifecta.

On Your Feet has a game called Three Favorites, in which participants list three things they like a lot and then combine two of them to form new business ideas. Mashing up Bollywood music and grocery stores led one group of clients to imagine a sound system on which mariachi bands play in the Mexican food section and cows moo in the dairy case.

There’s also Phone a Friend, in which a group brainstorms about a topic, like compensation. Then everyone in the group gets 15 minutes to reach a friend who works in a different industry and ask how he or she handles it. In one session, on staffing, a participant called a friend at the National Basketball Association, who told him about the 10-day contracts teams use to try out players. The person went back to the group and proposed that companies could use them, too.

The Second City got into the market in 2002. In the decades since its founding, it had built a nice little business doing entertainment for corporate parties. Then the Sept. 11 attacks happened, and that market dried up. The Second City found itself competing with Neil Diamond impersonators for scarcer dollars. So it, well, improvised.

Andrew Alexander and Len Stuart, the Canadian co-owners of the company, started a division to use improv to craft advertising campaigns. They hired an ad man named Tom Yorton to run it. Yorton, too, pivoted, pushing the company into something else entirely: corporate training. The division became Second City Works. It now has 35 full-time employees and taps a further 150 improv teachers, writers, actors, and directors. Second City Works also makes corporate-training films, called RealBiz Shorts.

“This all comes from our core—using the tenets of improvisation,” Alexander says. Altogether, The Second City has annual revenue of $50 million and is growing quickly.

Improv is one of hundreds of methods used to train people these days. Leaders and their workers are coached, lectured, numbed with PowerPoint presentations, and taken into the wilderness. Richard Olivier, son of Laurence, uses Shakespeare plays to teach leadership through a system he calls Mythodrama.

They are all essentially trying to get people to the same place. But Daniel Pink, author of a series of management books, including the best-seller To Sell Is Human, says improv is uniquely suited to our times. National Cash Register succeeded in the late 1800s because founder John H. Patterson required salesmen to memorize scripts that had proven results. These days, Pink says, anything that can be scripted can be automated. All that matters now is the unscripted stuff—unexpected questions, personal connections. “There’s only one technique out there for what to do when you don’t have a script: improv,” he says.

The improv folks keep things simple. Simple games, simple equipment, simple concepts. They don’t talk about even one sigma, much less six.Second City distills the whole practice down to “Yes, and ….” In improv, that’s how scenes build. One actor says, “An alligator came out of the swamp.” The next one says, “Yes, and the saddle in my garage just happened to fit him.” Saying “no” or “but” is out of the question in improv.

“‘Yes, but’ is just ‘no’ in a tuxedo,” says Alan Bernick, chief legal counsel at the window maker Andersen. He brought Second City in to help communicate the company’s code of conduct to its top 100 leaders in a memorable way.

For Hirsch, improv comes down to “everything is an offer.” In his book Do Improvise, Poynton (who now grows olives and teaches in Spain) writes: “To see everything as an offer means to regard everything that occurs as something you can use. To do that, you need to really notice what’s there, not just cruise through life thinking about lunch.”

All of improv is aimed at getting more ideas out of people’s minds and into the room. When it works, it’s brilliant. There’s a story that improvisers love to tell. While shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark in Tunisia, Harrison Ford got dysentery. On the day he was supposed to fight a scimitar-wielding assassin, he could barely stay out of the bathroom. So Ford improvised. After his opponent twirls and tosses his blades, Ford, looking spent, just shoots him. It’s one of the most memorable scenes in the movie.

Hirsch and Johnston say such genius is bottled up in every worker, and you don’t need Pareto charts or Kanban analysis or any other Lean Six Sigma method to tap it. Ali Khan agrees—and he knows what those things are. He can also see flowers in imaginary boxes, which may be a more valuable skill.